Mercury’s Rapid Revolution: The Fastest Year in the Solar System

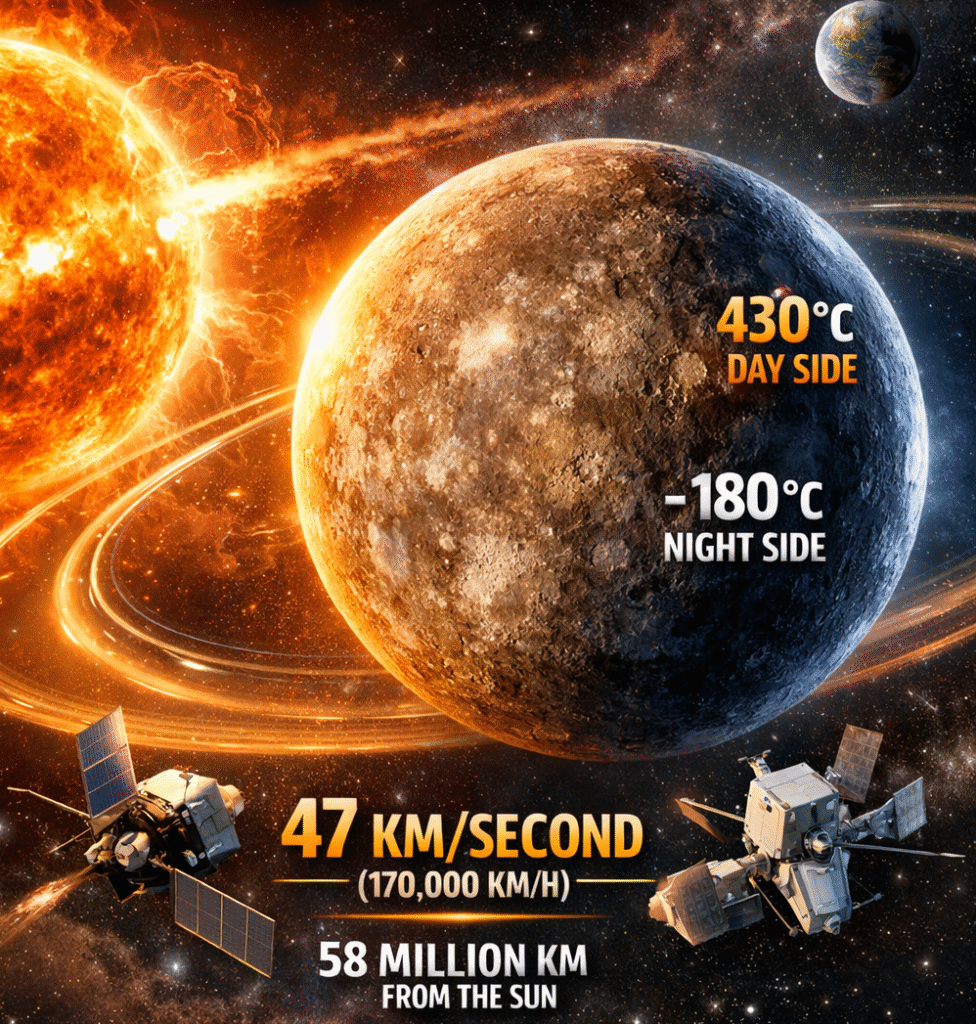

The planet Mercury completes a full orbit around the Sun in just 88 Earth days, making it the fastest-orbiting planet in the solar system. Scientists explain that this extraordinary orbital speed—averaging nearly 47 km per second—is driven primarily by Mercury’s extremely close distance to the Sun, where solar gravity is strongest. According to orbital mechanics, the closer a planet lies to the Sun, the greater the gravitational pull it experiences and the faster it must travel to remain in a stable orbit.

Mercury’s orbit is also highly elliptical, meaning its distance from the Sun changes significantly during each revolution. At its closest point (perihelion), the planet moves even faster as it swings around the Sun, while at its farthest point (aphelion) the speed decreases slightly. These variations were historically important in astronomy: precise measurements of Mercury’s orbital motion revealed small deviations that classical Newtonian physics could not fully explain. Those tiny irregularities were later accounted for by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, making Mercury a key testing ground for modern gravitational theory.

The planet’s short year creates unusual relationships between its rotation and revolution. Mercury rotates once every 59 Earth days, forming a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, meaning the planet completes three rotations for every two orbits around the Sun. As a result, a single solar day (sunrise to sunrise) lasts 176 Earth days, twice the length of a Mercurian year. Observers standing on the surface would see the Sun move in unusual patterns—sometimes appearing to stop, reverse direction briefly, and then continue across the sky—because of the interaction between Mercury’s rotation speed and its changing orbital velocity.

The rapid yearly cycle also contributes to Mercury’s extreme environmental conditions. With no substantial atmosphere to trap or distribute heat, the side facing the Sun during perihelion experiences scorching temperatures exceeding 430°C, while the night side can fall below –180°C. Because Mercury completes more than four orbits in a single Earth year, its surface undergoes repeated cycles of intense heating and cooling, which gradually fracture rocks and shape the planet’s rugged landscape of cliffs, ridges, and impact basins.

Modern planetary missions from organizations such as NASA and European Space Agency continue to monitor Mercury’s orbit with extraordinary precision. These measurements help scientists refine models of solar gravitational effects, study how planetary interiors respond to tidal forces, and better understand the formation of rocky planets close to stars—including similar worlds being discovered around distant solar systems.

Astronomers say Mercury’s 88-day year demonstrates how dramatically time scales can vary across the solar system: what humans call a “year” depends entirely on orbital distance, meaning the experience of time on different planets can differ by factors of hundreds or even thousands.