Astronomers Confirm the Milky Way’s Future Merger with Andromeda

Astronomers say the impending encounter between the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy is not a sudden crash, but a prolonged, awe-inspiring transformation that will unfold across billions of years—reshaping the local universe and redefining our galaxy’s future.

A Gravitational Attraction That Can’t Be Escaped

Both the Milky Way and Andromeda are massive spiral galaxies embedded in the Local Group, a small cluster of more than 50 galaxies bound together by gravity. Together, these two giants contain the majority of the group’s mass. For decades, scientists suspected that Andromeda was moving toward us, but modern observations using Hubble Space Telescope proper-motion data confirmed that its sideways motion is minimal. This means Andromeda is heading almost directly toward the Milky Way, making a collision unavoidable.

Adding to the complexity is the presence of dark matter halos—huge, invisible cocoons surrounding both galaxies. These halos extend far beyond the visible stars and are already interacting. In a sense, the merger has already begun at an unseen level, long before the galaxies’ bright disks touch.

What the Night Sky Will Look Like

In about 3–4 billion years, Andromeda will appear dramatically larger in Earth’s night sky, eventually stretching across a vast portion of the heavens. What is now a faint smudge visible to the naked eye from dark locations will become a dominant celestial feature, brighter and larger than the Moon appears today. Future observers—if any exist—would witness an ever-changing sky filled with overlapping star fields and glowing gas clouds.

Starbirth on a Grand Scale

As the galaxies interpenetrate, enormous clouds of gas and dust will collide and compress. This process is expected to ignite intense starburst activity, producing millions of new stars in relatively short cosmic periods. Some of these stars will be massive and short-lived, ending their lives as supernovae, enriching the new galaxy with heavy elements essential for planet formation.

At the same time, vast numbers of stars will be flung into new orbits, forming extended stellar streams and halos. The familiar spiral arms of both galaxies will gradually lose their structure, stretched and twisted by gravitational tides.

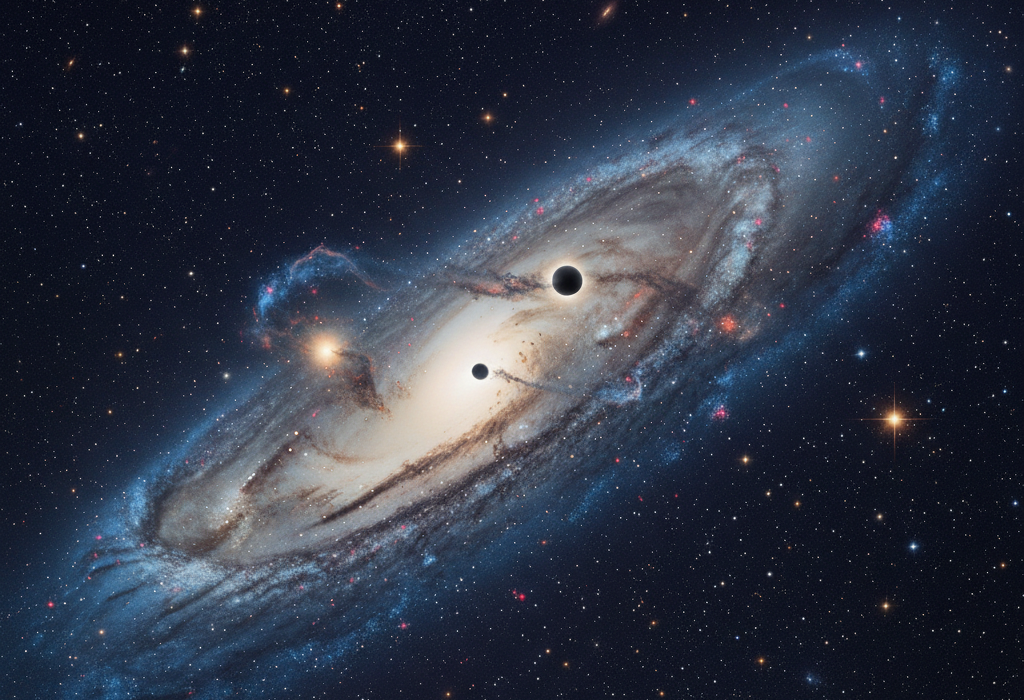

A Clash of Supermassive Black Holes

At the center of the Milky Way lies Sagittarius A*, a supermassive black hole about 4 million times the mass of the Sun. Andromeda hosts an even larger central black hole, weighing in at roughly 100 million solar masses. As the galaxies merge, these two giants will spiral toward one another, eventually forming a binary black hole system before finally merging themselves.

This final black hole merger will release enormous amounts of energy in the form of gravitational waves, rippling through spacetime—signals that future civilizations or detectors might observe long after the event has passed.

The Birth of a New Galaxy

After several close encounters and billions of years of gravitational settling, the chaos will calm. The end result will be a single, massive elliptical galaxy, containing hundreds of billions—possibly trillions—of stars. Its shape will be rounder and smoother, with little of the spiral structure that defines the Milky Way today.

This new galaxy will dominate the Local Group, while smaller nearby galaxies, such as the Triangulum Galaxy (M33), may also be absorbed during the process.

A Common Fate in the Universe

Far from being unusual, this galactic merger reflects a common evolutionary pathway. Many of the large elliptical galaxies seen across the universe are believed to be the products of similar mergers. By studying the future Milky Way–Andromeda collision through simulations, astronomers gain insight into how galaxies grow, age, and transform across cosmic time.

While humanity will not witness this event firsthand, the science is clear: our galaxy’s future is written in gravity. The Milky Way is not destined to drift alone through space, but to become part of a far larger and more complex cosmic structure—born from one of the universe’s grandest slow-motion collisions.