A Red Planet with a Blue Heart: The Science of Martian Sunsets

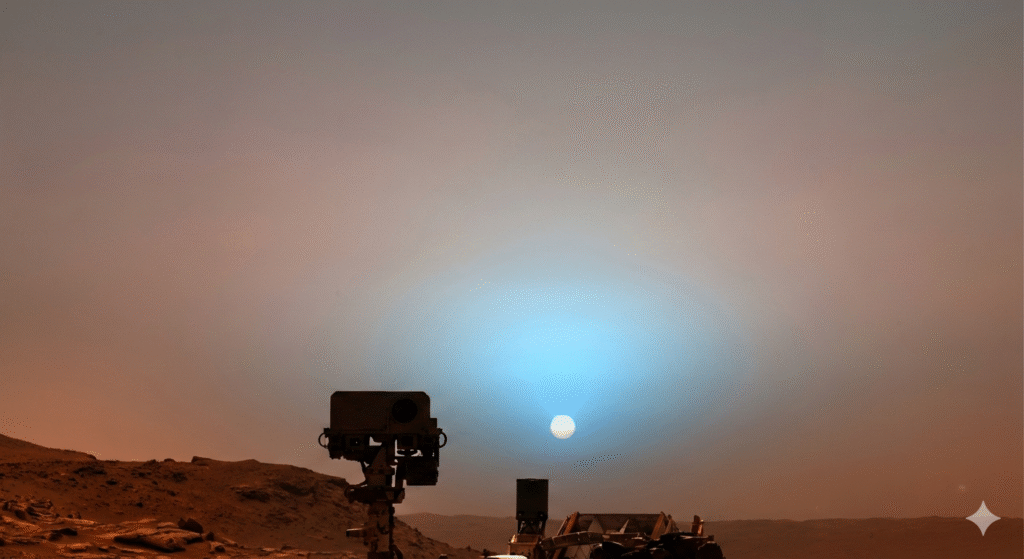

Standing on the surface of Mars at dusk offers a surreal reversal of the Earthly experience. While we are used to a blue sky during the day that bleeds into a fiery red and orange sunset, Mars does the exact opposite. On the Red Planet, the daytime sky is a murky butterscotch color, but as the sun dips toward the horizon, the area around it glows with a cool, ethereal blue.

Here is the detailed breakdown of why this phenomenon happens and how it differs from Earth.

The Science of Scattering: Why the Colors Flip

To understand the blue sunset, we have to look at how light interacts with the atmosphere. This is governed by two different types of “scattering.”

- Rayleigh Scattering (Earth): Earth’s atmosphere is composed of tiny gas molecules (nitrogen and oxygen). These molecules are very effective at scattering shorter wavelengths of light—blue and violet. During the day, blue light is scattered in every direction, making the sky look blue. At sunset, the light has to travel through much more atmosphere, scattering away the blue almost entirely and leaving only the long-wavelength reds and oranges to reach our eyes.

- Mie Scattering (Mars): Mars has a very thin atmosphere filled with fine silicate dust. These dust particles are much larger than gas molecules. Instead of scattering light in all directions, they perform “Mie scattering,” which filters the colors differently. These particles are the perfect size to scatter red light across the sky during the day, but they allow blue light to pass through more directly toward the observer.

The “Blue Glow” Effect

The blue color is most prominent in the forward-scattering direction. This means that if you are looking directly toward the sun as it sets, the blue light is passing through the dusty atmosphere with less interference than the red light.

As the sun approaches the horizon, the light has to pass through the thickest layers of dust. The dust particles absorb the red light and scatter it away, but they act as a sort of “filter” that lets the blue light penetrate through. The result is a distinct blue “halo” or glow that surrounds the solar disk.

What Would a Human See?

If you were standing on Mars, the sunset wouldn’t look like a neon blue neon sign. It is more of a pale, moody azure.

- The Sun’s Size: Because Mars is further from the sun than Earth, the sun appears about two-thirds the size we are used to seeing.

- The Transition: As the sun sets, the “butterscotch” sky fades into a dark, grayish-pink, while the area immediately surrounding the sun turns a clear, cold blue.

- The Duration: Because Mars has a thinner atmosphere but often holds dust high in the air, the “twilight” can last for a long time—up to two hours after the sun has actually set—due to sunlight reflecting off high-altitude dust.

History of the Discovery

We first confirmed this phenomenon through the eyes of our robotic explorers.

- Viking 1 (1976): The first lander to send back images of a Martian sunset, though the colors were difficult to calibrate at the time.

- Spirit and Opportunity (2004): These rovers sent back high-definition “postcards” that clearly showed the blue-tinted sun.

- Curiosity and Perseverance: Modern rovers have captured high-resolution video and even “blue sun” transitions, providing the most color-accurate look at the Martian horizon to date.

The blue sunset on Mars is one of the most hauntingly beautiful examples of how a planet’s atmospheric composition dictates its visual reality. While Earth’s sunset is a product of gas molecules, Mars’ sunset is a product of suspended mineral dust.

Here is the deep-dive technical and visual breakdown of this Martian phenomenon.

1. The Physics: Rayleigh vs. Mie Scattering

To understand the blue sunset, you have to understand two competing types of light scattering.

- On Earth (Rayleigh Scattering): Our atmosphere is thick and made of tiny molecules (Nitrogen/Oxygen). These molecules are much smaller than the wavelength of visible light. They are incredibly efficient at scattering blue light (short wavelengths) in every direction. This makes our daytime sky blue. At sunset, when the sun is low, light travels through more atmosphere; the blue is scattered away entirely, leaving only the reds to reach your eyes.

- On Mars (Mie Scattering): The Martian atmosphere is 100 times thinner than Earth’s, so Rayleigh scattering is negligible. Instead, the sky is dominated by micron-sized dust particles (primarily hematite and magnetite). These particles are roughly the same size as the wavelength of visible light. This triggers Mie scattering, which is “anisotropic”—meaning it doesn’t scatter light evenly in all directions.

2. The “Forward Scattering” Blue Halo

The key to the blue sunset is a phenomenon called near-forward scattering. * Martian dust is highly efficient at scattering red light away at wide angles. This is why the Martian sky looks reddish-pink during the day—you are seeing the red light that has been bounced around the atmosphere.

- However, these same dust particles allow blue light to pass through with very little deflection. When you look directly toward the setting sun, you are looking through a “tunnel” of dust that has filtered out the red light but allowed the blue light to pass straight through to your eyes.

- This creates a 10-degree cone of blue light immediately surrounding the sun’s disk, which tapers off into the rusty colors of the rest of the sky.

3. The Composition of the Dust

The dust isn’t just “dirt”; it is a complex aerosol.

- Size: The particles are generally between 0.5 and 3 micrometers in diameter. If they were any smaller, the sky would look more like Earth’s; if they were much larger, the sky would simply look grey or brown.

- Chemistry: The dust is rich in iron oxides (rust). These minerals have a specific “refractive index” that causes them to absorb blue light at high angles but reflect it at low angles.

- Ice Clouds: High-altitude water-ice or CO₂-ice clouds can intensify the effect. During the “Aphelion Cloud Belt” season, these ice crystals can add a crystalline shimmer to the sunset, occasionally making the blue appear more “electric” or pale white.

4. The “Long Twilight”

A Martian sunset lasts significantly longer than an Earthly one. On Earth, once the sun dips below the horizon, the sky darkens relatively quickly. On Mars, the dust remains suspended at very high altitudes (up to 40–50 km). Even after the sun has set from the perspective of a rover on the ground, its rays are still hitting the high-altitude dust. This light is reflected down to the surface, creating a twilight that can last for two hours. ### 5. How the Rovers “See” It When we look at photos from the Curiosity or Perseverance rovers, we are seeing through sophisticated digital eyes:

- Mastcam & Mastcam-Z: These cameras use Bayer filters (red, green, and blue pixels) just like a high-end DSLR, but they are calibrated for the harsh Martian light.

- Solar Filters: To take photos of the sun directly, the rovers use Neutral Density (ND) filters—essentially high-tech sunglasses—that reduce the sun’s intensity by a factor of 1,000 to prevent the sensors from being “blinded.”

- True Color vs. Enhanced: Most NASA images are “white-balanced” to show what a human would see. If you were there, the blue would not be a “neon” blue; it would be a soft, moody, pale azure glow that contrasts against a dark, grayish-pink sky.

Earthly Anomalies: The “Blue Moon”

On rare occasions, Earth experiences a similar effect. After massive volcanic eruptions (like Krakatoa in 1883) or intense forest fires, the atmosphere can become filled with particles of a very specific size (about 1 micrometer). For a short time, people on Earth see a blue moon or a blue sun for the exact same Mie-scattering reasons that are permanent on Mars.

casino slot https://elonbet-casino-game.com

Нужен трафик и лиды? сайт студии avigroup SEO-оптимизация, продвижение сайтов и реклама в Яндекс Директ: приводим целевой трафик и заявки. Аудит, семантика, контент, техническое SEO, настройка и ведение рекламы. Работаем на результат — рост лидов, продаж и позиций.

Thinking of signing up for V9Bet? Dangkyv9bet should have the registration details. Let’s see what they offer! dangkyv9bet

need a video? milan production company offering full-cycle services: concept, scripting, filming, editing and post-production. Commercials, corporate videos, social media content and branded storytelling. Professional crew, modern equipment and a creative approach tailored to your goals.

Продажа тяговых https://faamru.com аккумуляторных батарей для вилочных погрузчиков, ричтраков, электротележек и штабелеров. Решения для интенсивной складской работы: стабильная мощность, долгий ресурс, надёжная работа в сменном режиме, помощь с подбором АКБ по параметрам техники и оперативная поставка под задачу

Продажа тяговых https://ab-resurs.ru аккумуляторных батарей для вилочных погрузчиков и штабелеров. Надёжные решения для стабильной работы складской техники: большой выбор АКБ, профессиональный подбор по параметрам, консультации специалистов, гарантия и оперативная поставка для складов и производств по всей России

Актуальная ссылка площадки на рабочая ссылка кракен с защитой от фишинга и мошеннических копий сайта

Продажа тяговых ab-resurs.ru аккумуляторных батарей для вилочных погрузчиков и штабелеров. Надёжные решения для стабильной работы складской техники: большой выбор АКБ, профессиональный подбор по параметрам, консультации специалистов, гарантия и оперативная поставка для складов и производств по всей России

Продажа тяговых faamru.com аккумуляторных батарей для вилочных погрузчиков, ричтраков, электротележек и штабелеров. Решения для интенсивной складской работы: стабильная мощность, долгий ресурс, надёжная работа в сменном режиме, помощь с подбором АКБ по параметрам техники и оперативная поставка под задачу

Anyone tried Superphfb? I did. It’s alright. Nothing groundbreaking, but it’s got its charm. Some of the games are kinda catchy. Give it a quick browse: superphfb

networking made easy – Smooth navigation makes accessing key links quick and simple.

fresh strategy ideas – The layout supports discovering concepts without distraction.

learn with ease – Content is accessible and encourages curiosity.

modern finds hub – Clean design with a selection that feels current and thoughtful.

trusted bond resource – The presentation feels confident and reassuring from start to finish.

ValueCartOnline – Designed to make online shopping practical and budget-friendly.

EnterpriseAllianceHub – Presents a polished approach to forming effective enterprise partnerships.

shopping variety zone – Nice mix of products that encourages looking around.

ClickForBusinessTips – Easy navigation, lessons are highly useful and straightforward.

protected purchase hub – Security is a priority, making shopping smooth and worry-free.

EliteBuyPro – Clean interface, finding and purchasing items is easy.

TrustedBondInsights – Very informative, strategic bonds are explained clearly and reliably.

browse here – Simple structure, navigation works well and information is accessible

SmartSavingsCart – Highlights smart and value-focused shopping experiences.

online access – Content is organized, layout is clean, browsing is effortless

SecureBuyPro – Smooth and intuitive, online purchases are hassle-free.

alliances insight platform – Useful tips, simplifies how alliances operate in different markets.

Well Laid Out Site – Stumbled upon this and was pleasantly surprised by the clarity

tavro destination – Smooth and tidy interface with clear, well-structured information

check nexra – Well-structured sections, fast response, first impression is very positive

TrustConnectHub – Organized and informative, networking globally is efficient and simple.

ValueCartOnline – Designed to make online shopping practical and budget-friendly.

korixo hub – Straightforward layout that welcomes easy use

mexto corner – Pleasant browsing with well-organized content

BrixelFlow – Smooth pages, neat interface, and browsing is effortless.

Kavion Path Express – Smooth interface, fast pages and product info clear and readable.

RixarFlow – Smooth browsing, responsive pages, and information easy to find.

QuickClickPlavex – Clear interface, responsive pages, and navigating products is easy.

actionpowersmovement link – Pages are structured logically, text is readable, and browsing feels natural

zorivo web portal – Navigation simple, content easy to scan and pages loaded instantly.

olvra access – Fast-loading pages with well-structured and trustworthy text

PortalMorixo – User-friendly interface, responsive pages, and browsing was very smooth.

focusdrivesmovement web – Clear structure, smooth scrolling, and information is easy to digest

UlvaroFlow – Fast response, product pages are clear, and navigation feels simple.

XaneroCenter – Fast-loading pages, design neat, and navigation smooth throughout.

visit nixra – Clean layout and intuitive navigation, really enjoyed exploring

focusbuildsenergy hub – Simple layout, navigation is intuitive, and content is easy to read

OpportunityVisionHub – Easy-to-follow and informative, long-term options are simple to recognize.

click hub – Fast loading, everything displayed as it should without issues.

UlvionLink – Fast-loading pages, neat design, and content easy to follow.

trusted hub – Everything functions smoothly, clean layout made it easy to browse

Velixonode Lane – Layout clean, navigation effortless and site feels trustworthy overall.

XelarionAccess – Pages responsive, content clear, and shopping is effortless.

Pelixo Capital hub – Well-organized sections, clear explanations, and browsing is effortless.

Qorivo Bonding Network – Professional design, readable text, and navigation flows naturally.

bryxo homepage – Clean and simple layout where everything works as expected

explore directionunlocksgrowth – Overall clean design, easy navigation, and information is clear and accessible

Mivon homepage – Clear explanations and an honest tone stand out immediately.

Qorivo Holdings Online – Organized content, readable layout, and overall browsing feels natural.

EasyClickQori – Layout professional, pages load fast, and all content is simple to navigate.

check cavix – Smooth visit, nothing feels crowded and the content is helpful

zalvo.click – Well-structured site, easy-to-find content, and pages respond quickly

DecisionClarity – Advice is clear and actionable, helping users make choices with confidence.

pelvo network – Minimal design, clear layout, and content feels approachable and neat

Brixel Capital digital presence – The site communicates confidence through consistent tone and design.

morix hub – Pleasant layout with readable text and navigation that feels natural

BestDealSpot – Practical platform, locating deals online is easy and reliable.

quorly page – Pages load efficiently and information is straightforward and useful

Velixo Trust Group – Layout is clean, explanations are simple and easy to grasp.

Open capital homepage – Early impression is positive, seems worth reviewing in more detail.

mivox source – Smooth layout, content is clear, and the pages are easy to move through

Trustline homepage link – Simple layout, quick loading, and content that seems up to date.

TrustedPartnerHub – Well-organized site, gives confidence in professional partnership decisions.

Bond group site access – Found it during exploration, information feels naturally presented.

xelivotrustgroup.bond – The layout is straightforward and moving through pages feels smooth.

VexaroUnity Main Site – Fresh approach, values are communicated transparently without exaggeration.

Partners – Partner information is organized logically and easy to access.

See holdings platform – Clear structure and menus guide you through the content smoothly.

xeviro bonding platform – Smooth loading makes the experience feel dependable.

rixon info – Organized layout, smooth scrolling, and content is accessible quickly

ReliableCartCenter – Simple and clear, shopping online is quick and reliable.

meaningful learning hub – Content feels motivating and helps turn ideas into practical takeaways.

Platform overview – Easy-to-follow structure, navigation is fast, and details are straightforward.

kavlo site – Modern styling paired with navigation that works without friction

TrustedCartHub – Reliable and well-structured, checkout is fast and worry-free.

Professional bond page – Simple layout, easy to explore, and information is reliable.

Events – Clear design, smooth navigation, and event information is easy to follow.

Testimonials – Feedback is displayed in a neat, professional manner that’s easy to read.

Check capital details – Organization is logical, making it simple to find relevant topics quickly.

Kavionline official page – Simple site navigation, accessible design, and well-presented content.

Bond services online – Easy-to-use interface, fast pages, and content is quick to read.

LongTermConnectionsOnline – Structured and helpful, corporate networking is accessible and reliable.

pathway to success hub – Organized layout supports easy decision-making for next steps.

bavix link – Good first impression, content flows well and makes sense

Home – Clean layout with fast navigation and information that’s easy to locate.

yaverobonding.bond – Nice experience overall, pages are organized and fairly user friendly.

talix – Clean design, navigation is intuitive, and content is easy to follow

See trust platform – Content is straightforward, offering a solid base for online learning.

GlobalNetworkingGuide – Clear and professional, building international relationships is effortless.

bond info hub – Navigation is seamless, and the layout feels straightforward.

trusted resource – Smooth performance, concise explanations, very approachable layout

Partners – Partner information is organized clearly, and pages load quickly for effortless exploration.

trusted site – Navigation is smooth, content is concise, and overall presentation is strong.

Learn more here – Simple interface, responsive design, and details are clear and easy to locate.

quick link – Straightforward interface and responsive pages, enjoyable to browse

investment portal – Layout is neat, text is readable, and pages respond without delay.

Trust overview – Everything is presented neatly, helping users understand the details quickly.

official site – Navigation is smooth, and information is presented clearly throughout.

ClickXpress – Pages responsive, layout organized, and finding content was effortless.

zylavoline platform – The site responds quickly, presenting information in a straightforward way.

Portfolio – Visual content is displayed neatly, providing clarity and a pleasant browsing experience.

zorivoline network – Gives off early potential that merits occasional follow-up.

legacybridge.bond – Well organized, content is engaging and legacy themes resonate naturally.

worlddiscovery.bond – Vibrant layout, content invites curiosity and makes exploring new ideas simple.

EasyClickMorixo – Smooth pages, clear layout, and product info easy to understand.

CalmCornerGoods – Relaxed site layout with fast checkout.

boutique wood atelier – Everything feels cohesive and calm, with a strong focus on visual harmony.

Vector Navigator – Layout and visuals feel professional, making content accessible.

Bonded Unity Stream – Smooth navigation, messaging reinforces collective focus and clarity.

visit zorivotrustco – Comes across as well-structured with confidence-building details throughout.

creativehub.bond – Bright design, site encourages exploration and presents ideas in an engaging way.

Learn more here – Content is easy to scan, and pages feel polished and user-friendly.

MeadowGroveGoods – Clear product layout helps users shop efficiently.

QuickPlivoxClick – Smooth pages, organized layout, and checkout process easy to follow.

Official trust resource – The pages are responsive and navigation is smooth throughout.

Community – Interactive sections are organized intuitively, encouraging smooth participation and engagement.

sunny outlet finds – A bright presentation paired with a smooth flow makes shopping feel effortless.

Anchor Capital Bridge – Clean interface, pages load easily and inspire trust through clarity.

zylavobond access – Simple structure and clear labeling make key points easy to understand.

actionpath.bond – Modern design, navigation is simple and content inspires steady movement toward objectives.

EasyClickZaviro – Layout minimal, navigation simple, and product details easy to find.

Bonded Framework Access – Professional structure, framework concept is easy to grasp at a glance.

pine lifestyle shop – Everything feels thoughtfully arranged, and the descriptions are clear and helpful.

clarity advantage – Layout is tidy and ideas are presented in a way that’s easy to understand.

Main project page – First look is positive, with readable content and a well-structured layout.

alliantfocus.bond – Clear layout, content emphasizes foundational values in a straightforward manner.

ironpetalcollection.shop – Simple and clear, layout highlights products well and checkout is uncomplicated.

VixaroEase – Smooth navigation, pages open quickly, and categories easy to browse.

Direct site access – Clear information and uniform branding help build trust with visitors.

focus pathway – Language is purposeful, creating a sense of momentum and clarity.

capitalbondinitiative.bond – Design feels inviting, collective growth ideas are easy to grasp.

official portal – Smooth navigation, clear sections, and no distracting elements.

ZorivoEase – Pages load fast, interface minimalistic, and navigation is straightforward.

Bonded Legacy Center – Layout is polished, legacy theme is clear and content feels reliable.

TrivoxCenter – Pages opened quickly, design clean, and browsing was intuitive.

rustic value store – Clear organization and concise descriptions support an easy shopping flow.

Check platform details – Information is presented logically, with a clean and professional appearance.

solid investment page – Clear, practical, and well-laid-out, perfect for bond exploration.

northwindbazaar.shop – Friendly design, browsing products is smooth and checkout is reliable.

urbanwavecentral.bond – Streamlined design, content is readable and the site feels engaging overall.

QuickClickXylor – Pages responsive, layout tidy, and content easy to locate.

aurumlane style hub – Visually appealing, the site is easy to use and flows nicely from page to page.

value shopping hub – Excellent selection, prices are reasonable and browsing is effortless.

shoproute centerpoint – Simple interface, platform helps compare items quickly and efficiently.

discover solutions click – Fun and engaging, site encourages creative problem-solving today.

ClickXanix – Smooth interface, content loads fast, and browsing feels intuitive.

midnight cove goods online – Refined dark look, site is easy to use and checkout feels reliable.

ZorlaCenter – Layout professional, pages responsive, and product info easy to locate.

Explore new ventures hub – Layout is clean and encourages easy browsing.

alliance planning click – Easy-to-use platform, provides practical tips for corporate partnerships.

safe bonds hub – Professional and secure presentation makes bond details easy to digest.

XelivoPortal – Pages opened instantly, navigation was smooth and the content seemed trustworthy.

daily achievement site – Inspires progress through simple, repeatable actions.

buy easy hub – Efficient layout, online shopping feels effortless and stress-free.

Mavero Trustline main homepage – Organized design, content is concise, and navigation feels natural.

skill advancement portal – Helpful advice, encourages incremental progress over time.

Innovation planning platform – Browsing is simple, and the design is visually appealing.

purchase smart portal – Clean layout, makes finding and buying items straightforward.

life planning portal – Feels inspiring, makes mapping out goals straightforward.

smartbuy shoproute – User-friendly layout, shopping flows naturally and comfortably.

Trusted networking resource – The site gives a positive impression with organized and readable sections.

Learn and grow site – Easy navigation and helpful resources make studying enjoyable.

Smart online store hub – Simple interface and practical functions make running a business smooth.

Networking collaboration platform – Smooth experience with a clear and practical idea.

Professional learning space – Easy-to-read sections make browsing comfortable.

Better solutions hub – The site feels engaging and encourages creative thinking right away.

networkingcentral – Really simple way to meet new people and expand your social circle.

valuefocusedpartnerships – Helpful alliance concepts that support long-term business stability.

planning and strategy page – Clear guidance that helped refine workflow and improve results.

Friendly learning site – Nice setup, it seems designed to make learning less intimidating.

essentialsquickshop – Fast, intuitive platform, really convenient for everyday needs.

businessconnectionshub – Platform is intuitive, connected me with the right experts quickly.

partnershipsuccesstools – Clear and practical guidance, really helped with organizing partnership projects.

Enduring business solutions – Well communicated, the long-term focus feels sincere.

corporateconnectionclick – Platform is efficient, allowed me to establish multiple connections quickly.

collabworkplatform – Excellent features that enhanced team communication and workflow.

Explore Possibilities – Motivating and clear, users can quickly find and assess options.

startupframeworkguide – Clear guidance and dependable insights for structuring new companies.

relationshippro – Clear and effective tips, strengthened my networking skills.

Collaborative Learning – Friendly and motivating, site encourages exchanging knowledge constructively.

smartshopnetwork – Very user-friendly, I completed my purchases without any problems.

Improve Every Day – Engaging and motivating, posts make developing skills feel simple and doable.

Clinical massage services – Calm interface, the therapy information is concise and reassuring.

networkingtoday – Great environment to meet decision-makers and industry leaders.

RenovSystem bathtubs – Clear layout, the product info is simple to read and evaluate.

corpstreamline – Practical tools that improved team efficiency instantly.

digitalmarketplace – Very intuitive, purchasing items online was seamless.

Find Answers and Ideas – Clear and practical, resources simplify problem-solving effectively.

Straightforward web page – Clear and quick, nothing feels bloated.

trusted deal source – Deals were simple to locate and the process was efficient.

strategicpartneradvice – Suggestions are solid, made long-term partnership strategies much clearer.

valuegrowthalliances – Platform is useful, gave actionable ideas for enterprise partnerships.

collabcentral – Very helpful, made project coordination much easier for everyone.

alliance planning toolkit – Well-structured guidance for developing professional alliances.

shoppinghub – Great deals, very simple and hassle-free checkout.

corporateframeworksolutions – Advice here is actionable, really helped improve our business operations.

retailzone – Convenient and responsive, shopping online feels effortless.

smartcommerce – Easy interface, allowed quick navigation and fast transactions.

fastbuyportal – Practical and easy to use, checkout was a breeze.

teamconnecthub – Collaboration is seamless, helped our teams work together more effectively.

easyshoppingportal – Smooth experience and trustworthy delivery every time.

connectbiznetwork – Simple and reliable platform, made connecting with colleagues very straightforward.

professionalgrowth – Very helpful, made skill-building easier and faster.

partnershippath – Useful guidance, helped coordinate team efforts efficiently.

bizadvancer – Very reliable, helped improve planning and strategy efficiency.

digitalbuyhub – High-quality products and a very smooth checkout experience.

teamworkstrategies – Advice on professional collaboration is useful, helped optimize team performance fast.

Anthony Dostie building portfolio – Easy-to-follow layout, professional and inspires confidence right away.

valuecartonline – Efficient shopping site, really convenient for finding and purchasing products.

smartbusinessmoves – Business strategies are actionable, really improved planning efficiency.

artsy glass page – Enjoyed the look and feel, craftsmanship stands out.

innovation portal – The site is well organized, and tech content is presented clearly.

Salt n Light productions – The work is impressive, narratives feel personal and emotionally strong.

Andrea Bacle photo collection – Lovely imagery throughout, every photo has a gentle, authentic feel.

ZylavoClick – Layout is modern, and navigation is effortless throughout.

XylixStudio – Easy to navigate, everything feels organized and accessible.

VixaroShopPlus – Very satisfied with the fast delivery and fully functional items.

RixaroTracker – Interface is intuitive and resources are easy to access.

BaseHub – Clean layout ensures users find services without hassle.

NaviroEdge – Keep tasks under control with intuitive tracking features.

MavroBase – Works flawlessly, very intuitive and consistent in performance.

morixo trustco guide – Layout is polished, and trust information is easy to read and structured well.

RixaroFlow – Clear interface and helpful guidance, excellent for newcomers.

RavionBase – Layout is tidy, and product details are easy to understand.

QunixPro – Smooth interface, quickly found all the information I was looking for.

ZaviroBondGuide – Easy to move through the site, all resources were clearly visible.

zaviro capital services – Clean and professional, making it easy to grasp capital opportunities.

RixvaStudio – Straightforward navigation, everything works smoothly and feels organized.

TrixoAssist – Customer service provided clear and detailed answers in no time.

LixorBase – The information is well-organized, making key insights simple to digest.

PureValuePoint – A motivating site that helps ideas flow easily.

a href=”https://qulavoholdings.bond/” />QulavoEdge – Easy to understand options and a very trustworthy interface.

PlorixSphere – Clear structure, makes finding what you need fast and simple.

HoldingsView – Accurate insights simplify analysis and planning.

OrvixPoint – Loved the simple guidance; features are very easy to use.

BondNavigator – Insightful posts keep me engaged and returning often.

PlixoPro – Minimalist interface, all sections are easy to understand and use.

VelvixPoint – Everything is explained clearly, which saved a lot of time.

RavionFinance – Investment information is straightforward, and site performance is excellent.

click to view – Organized pages and readable content make exploring simple and fast.

main platform – Browsing is straightforward, and pages load cleanly for easy reading.

visit quixo – Dropped in by chance and everything made sense right away, nice experience.

vexaro info – Random visit, but browsing is easy and content is well presented.

trustco information – Pages are well-structured and content is presented clearly for easy access.

krixa network – Clear pages, intuitive navigation and information is well-structured.

check this out – Pleasant experience overall, content loads fast and stays relevant.

zylvo review – Simple structure, pages load fast and information is presented professionally.

mivarotrustline portal – Layout is clear, navigation is smooth and content is easy to follow.

core information – Professional layout with easy access to useful details.

discover qunix – Simple layout, navigation is fast and important information is easy to locate.

quvexatrustgroup site – Organized design ensures visitors can navigate without frustration and trust the content.

explore kryvoxtrustco – Clean design, content is easy to follow and pages respond fast.

main trust site – Brief visit, but the straightforward design stood out.

orvix access – Browsed by chance, but design keeps finding information very simple.

pexra dashboard – Simple layout, navigation is quick and important information is clear.

Discover Aurora – Amazing finds paired with excellent deals every time.

core information – Everything is organized clearly and responds without delay.

BrightBargain – Fantastic deals, I find amazing products every time I visit.

charmcartel.shop – The accessories are chic and the site is super intuitive to use.

plorix link – Browsed smoothly, content is well-presented and layout feels professional.

glintaro.shop – Fantastic collection of one-of-a-kind items, always a pleasure to shop here.

explore holdings site – Layout is clean and information is structured logically for easy understanding.

Natural hub – Love the variety and the fresh, natural vibe of the site.

Quick browse – Lots of products and smooth navigation throughout.

BrightBargain online – Perfect place for affordable shopping, I can always find a good deal.

collarcove.shop – Wonderful collars and accessories, shopping is quick and hassle-free.

crispcrate.shop – Such a great place for unique items, and the shopping experience is simple.

zexaroline – Found this through a link, stayed longer because layout works.

morvex access – Organized layout, pages load quickly and information is presented clearly.

this bond page – Solid first impression, site feels structured and professional.

yavex online – Pleasant experience, content is accessible and the design is minimal.

Auroriv hub – Stylish and easy-to-navigate site with lots of interesting items.

glintgarden.shop – A gardener’s paradise, filled with the best products for every need!

crystalcorner2.shop – A must-visit for crystal lovers, great quality gems and beautiful designs.

zexarotrust online – Easygoing layout with content that doesn’t overload you.

xorya explore – Landed here randomly, interface is neat and details are very easy to understand.

glintvogue.shop – Never run out of stylish options here, an excellent shopping experience!

curtaincraft.shop – Perfect for all your curtain and textile needs, amazing quality.

freshfinder.shop – Fresh, interesting, and unique finds every time, I can’t get enough of this site!

Briovanta Essentials – Great unique products and a seamless browsing experience.

Bag picks – Stylish, trendy, and always fun to shop through.

covecrimson.shop – Bold and high-quality items, this store never disappoints!

charmcartel.shop – Unique designs and fast navigation, love shopping here every time.

gardengalleon.shop – Highly recommend for gardeners, it’s full of great products to elevate any garden.

cypresschic.shop – Gorgeous products with a chic flair, and browsing the site is effortless.

Shop with ease – Everything feels intuitive and deal-focused.

Briovista World – Love the elegant design and variety of products, makes shopping here so enjoyable.

Beauty hub – High-quality skincare products with effortless browsing.

cozycarton.shop – Great selection of cozy items, whether you’re gifting or indulging yourself.

gemgalleria.shop – An impressive collection of gems and jewelry, ideal for birthdays, anniversaries, and more!

dalvanta.shop – Great collection of distinctive products! It’s always so easy to find what I need.

Brivona Finds – Love the clear and easy-to-navigate layout, it’s a smooth shopping experience.

kavix site – Simple, neat interface helps users get the details they need without confusion.

Home essentials – Beautiful baskets and practical decor make this site a must-visit.

gervina.shop – Great finds for modern home decor, perfect for updating your space!

charmcartel.shop – Love the stylish pieces and the website is very organized for easy browsing.

Astrevio style – Sleek design that gives off a very current vibe.

Hardware Harbor Store – Nice experience overall, products were easy to find and paying was quick.

Brondyra Boutique – Love the trendy products and how quick and easy the checkout is.

navirotrack page – Well-structured design ensures content is easy to find and looks credible.

Spa essentials – High-quality products that make every bath feel special.

goldgrove2.shop – Perfect place to find beautiful, rare finds, I always leave happy.

gingergrace.shop – Always something new and interesting to discover, a truly special shopping experience!

dorvani.shop – A fantastic place to shop for products that are both trendy and practical!

charmcartel.shop – Amazing accessories for every occasion, the site is so easy to use.

zorivohold hub – Stumbled upon this site, and it instantly felt polished and trustworthy.

buildbay.shop – A must-visit for DIY lovers, fast and easy shopping experience.

luggagelotus online store – Easy to explore, products look strong and selection is clear.

online henvoria – Pleasant to look around, finding items didn’t take long.

browse trixo – Well-laid-out pages and clear sections make finding info effortless.

craftcurio.shop – A must-visit for any crafter, it’s full of innovative and fun supplies!

dorvoria.shop – Great selection, fast shipping, and a pleasant shopping process!

greenguild.shop – Perfect for anyone looking for green products, the site is so easy to navigate.

charmcartel.shop – Stylish and unique items, the site makes shopping very enjoyable.

caldoria.shop – Such a well-curated store, I always have a great time shopping here.

Luggage Lotus Finds – User-friendly site, items are well-made and browsing feels smooth.

cratecosmos.shop – Fantastic variety of home accessories, and the site navigation is top-notch!

check rixarotrust – Simple interface allows information to be absorbed quickly and easily.

Cool arcade spot – Feels fresh and entertaining every time you visit.

Homely Hive Shop – Cozy atmosphere, everything felt simple and pleasant to explore.

Beard Barge online – Fantastic products and a smooth shopping experience every time.

glamgrocer.shop – Love the stylish designs and functional products, shopping here is always a pleasure!

charmcartel.shop – Great variety of chic accessories, shopping is quick and simple.

grovegarnet.shop – A wonderful mix of products, I love coming here to see what’s new.

Lunivora Boutique – Clean layout, fast performance and products look appealing.

Premium finds – Easy to explore and consistently impressive items.

cozy hollow shop – Came upon this site, pricing seems fair and transparent.

luxfable boutique online – Fashionable design, smooth experience and responsive pages.

curated goods store – Browsing was fast, selection feels thoughtfully put together.

Maple Merit Hub Store – Easy-to-navigate site, items are categorized and browsing feels solid.

harborhoney.shop – Such beautiful products! A must-visit for special events.

modern iris shop – Nice structure, locating products didn’t take long.

driftdomain.shop – Excellent site with a fantastic selection of unique finds.

Marigold Market Online Hub – Smooth browsing, items are easy to navigate and checkout feels seamless.

jenvoria marketplace – New here, pages loaded clean and the purchase steps seem easy.

marketmagnet store – Smooth interface, items are easy to find and descriptions are informative.

Office Opal Essentials – Browsing office items was smooth thanks to the organized and neat layout.

Chic Boutique – Elegant outfits, navigating the store feels easy.

elvarose.shop – A lovely assortment of items, perfect for decorating any room.

Paws Pavilion Store – Fun pet selection, pages load smoothly and buying is easy.

Muscle Myth Catalog – Clear product descriptions, authentic-looking items, and fair pricing.

Run River Online – Sleek look, site is intuitive and the buying process felt effortless.

Olive Outlet Boutique – Great range of items, fair pricing, and checkout was smooth.

Skin Serenade Finds – Fantastic products, navigation is straightforward and buying items is simple.

Spruce Spark Gems – Cheerful aesthetic, site is easy to navigate and checkout went perfectly smooth.

Vive Spot – Lots of options, checkout process was effortless.

Pantry Picks – Items are laid out clearly, shopping feels relaxed and effortless.

Poplar Prime Corner – Modern look, browsing products was smooth and intuitive.

Neon Notch Online – Eye-catching visuals make browsing fun, the personality is unique.

Ruvina Deals – Modern layout, browsing products is straightforward and shopping was enjoyable.

QuillQuarry Online – Unique finds, navigating the categories was smooth and effortless.

Skynaro Spot Picks – Trendy collection, site is user-friendly and item descriptions are helpful.

Starlight Hub Finds – Stylish interface, product info is clear and navigation is simple overall.

Pearl Pantry Hub – Straightforward design, pantry shopping was smooth and easy.

NeoVanta Essentials – Items are interesting, and exploring the site felt intuitive.

Quoralia Select – Attractive design, product info is clear and browsing feels smooth.

Stitchery Favorites – Elegant interface, products are displayed well and shopping was quick.

Visit Marqvella – Everything about this shop feels thoughtfully put together and stylish.

Plaza Product Picks – Had fun exploring the catalog, photos are clear and info is easy to read.

Prime Pickings Storefront – Diverse selection, browsing and choosing items was simple and pleasant.

Nook Narrative Selection – Carefully curated items combined with storytelling create an immersive experience.

fetchfolio.shop – Great accessories for every taste, the selection is always spot-on.

Quoravia Central – Easy-to-use interface, shopping categories are clear and checkout is straightforward.

SleekSelect Collection – Clean layout, items are clearly shown and shopping is simple and smooth.

Suave Basket Corner Picks – Sleek and stylish, product info is clear and checkout was straightforward.

Palvion Spot Picks – Easy navigation, browsing and finding items is enjoyable.