Breakthroughs in Detecting Alien Atmospheres

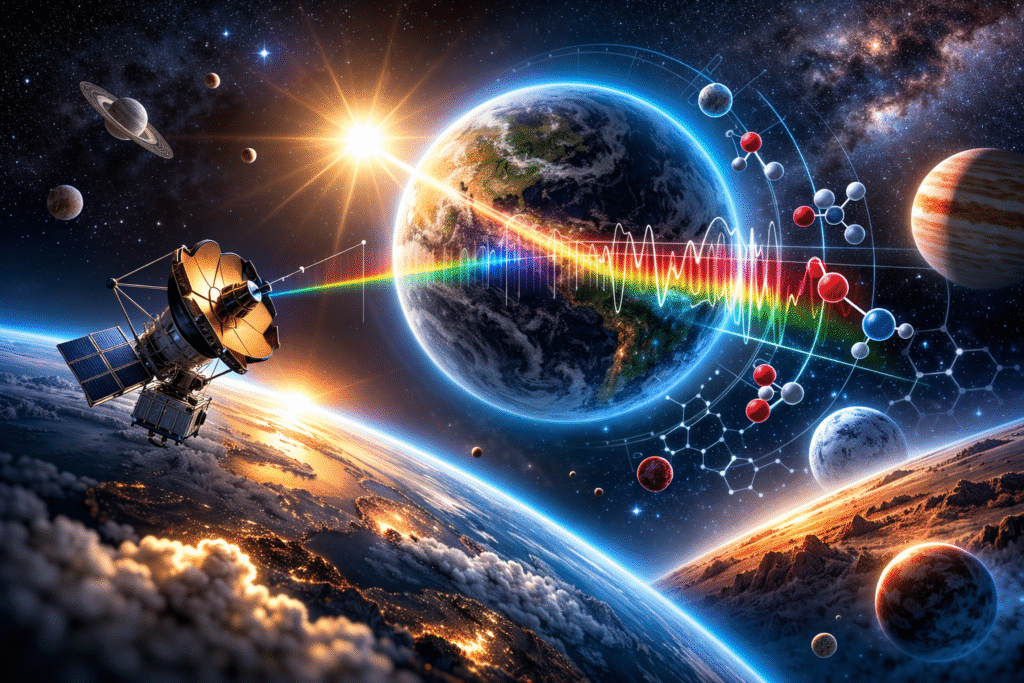

Detecting alien atmospheres more precisely, the atmospheres of exoplanets has transformed from science fiction into one of the most advanced frontiers of modern astronomy. The core idea is simple but powerful when a planet passes in front of its host star, a tiny fraction of starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere. That light carries chemical fingerprints. By analyzing these fingerprints, scientists can identify gases such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane and even more complex molecules.

The most important technique driving breakthroughs is transmission spectroscopy. During a planetary transit, astronomers measure how different wavelengths of starlight are absorbed. Each molecule absorbs light at specific wavelengths creating a spectral pattern that acts like a barcode. The precision required is extraordinary often detecting changes of less than one percent in starlight. Improvements in detectors, calibration methods and noise reduction have dramatically increased sensitivity over the past decade.

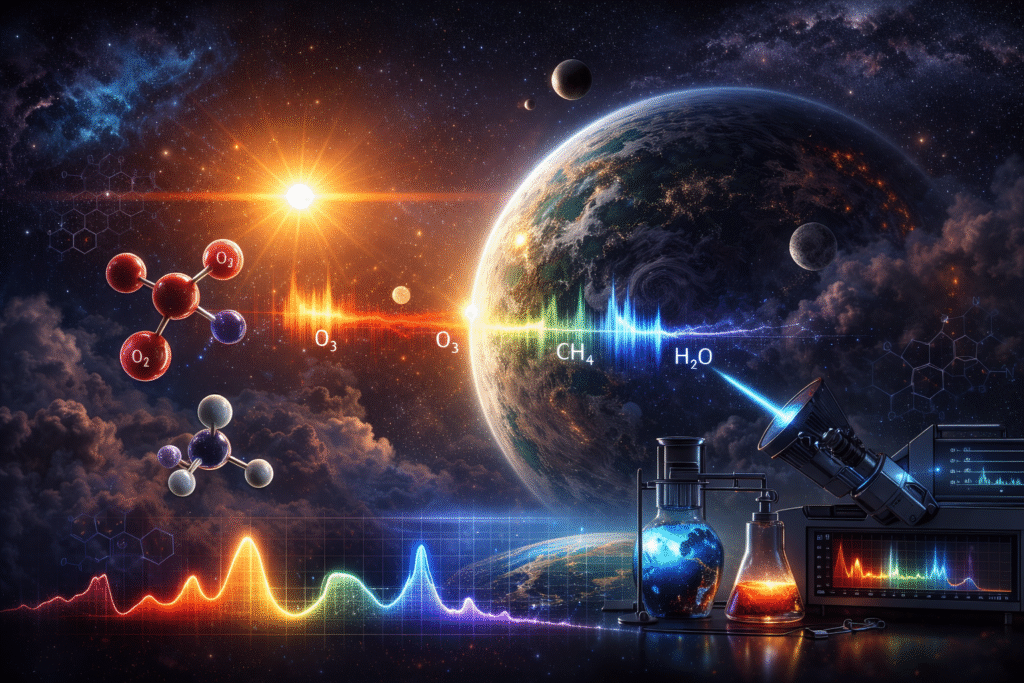

A major leap came with space-based observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope. Its infrared capabilities allow scientists to detect molecules that are difficult or impossible to measure from Earth due to atmospheric interference. Webb has already confirmed water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane and sulfur dioxide in multiple exoplanet atmospheres. Its ability to observe in the mid-infrared range enables far more detailed chemical inventories than previous telescopes.

Before Webb, the Hubble Space Telescope played a pioneering role. It provided the first detections of atmospheric sodium and water vapor in hot Jupiters gas giants orbiting very close to their stars. Although Hubble’s instruments were not originally designed for exoplanet studies, innovative analysis techniques allowed astronomers to extract atmospheric signals from subtle variations in starlight.

Ground-based observatories have also contributed significantly. Facilities like the European Southern Observatory operate extremely large telescopes equipped with high-resolution spectrographs. These instruments can measure Doppler shifts and isolate atmospheric signals even in the presence of Earth’s own atmospheric absorption. Adaptive optics systems correct for atmospheric distortion, sharpening the data quality.

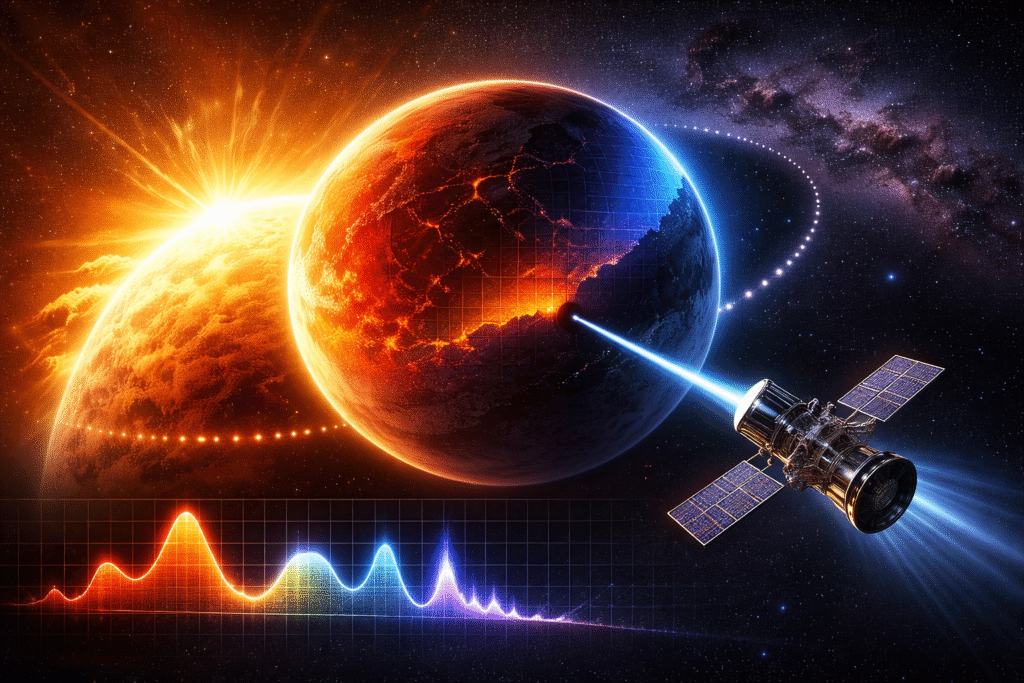

Another breakthrough method is emission spectroscopy used when a planet passes behind its star (a secondary eclipse). By comparing the total light before and during the eclipse, scientists isolate the planet’s emitted or reflected light. This reveals temperature profiles, thermal structures and sometimes even atmospheric circulation patterns. For hot exoplanets, researchers can map temperature differences between day and night sides.

Direct imaging is an emerging frontier. Instead of relying on transits, astronomers block out starlight using coronagraphs or starshades to directly capture faint light from orbiting planets. This technique is especially promising for studying young, massive planets far from their stars. Future missions aim to apply this method to Earth-sized planets in habitable zones where signs of life might be detectable.

One of the most exciting goals is the search for biosignatures chemical combinations that could indicate life. Oxygen, ozone, methane and water vapor together in disequilibrium could suggest biological processes. However, interpreting these signals is complex because non-biological processes can sometimes mimic them. Researchers now use atmospheric modeling, climate simulations and laboratory spectroscopy to better distinguish true biosignatures from false positives.

Machine learning and advanced data analysis are accelerating discoveries. Modern algorithms can separate stellar noise, instrumental effects and atmospheric signals more effectively than traditional methods. This allows weaker spectral signatures to be detected and increases confidence in atmospheric identifications.

Looking ahead, next-generation observatories like the European Extremely Large Telescope will further enhance sensitivity. With mirrors nearly 40 meters wide such telescopes will collect far more light, enabling the study of smaller and cooler planets. Combined with future space missions, they may allow detailed atmospheric characterization of Earth-sized worlds orbiting nearby stars.

In essence, the field has moved from merely detecting exoplanets to chemically analyzing them. The breakthroughs are not just technological they represent a shift in humanity’s capability to probe distant worlds for climate, chemistry and potentially life. The next decade is expected to refine these methods further, bringing us closer to answering one of the most profound questions: “Are we alone in the universe?”